Climate projection models play an important role in predicting the future rate and magnitude of climate change. Reconstructing the palaeoclimate and understanding the drivers of past climatic events is essential to validate and improve these projections. We caught up with the team, James English, David Warnes, Harry Williams and Megan Picken, to discuss the background to their project, their experiences in the field, and their key research findings.

What is the background to your fieldwork? What drew you to the project?

We all had an interest in reconstructing past environments using various proxies. Our expedition aimed to fill a knowledge gap that existed regarding past environmental conditions in the Sayan Mountains. It is important to understand how climate has changed in this region in the past as well as attempting to understand what caused those changes. This knowledge can then inform predictions about future climate change and its effects.

What questions did you set out to answer? What did you find out?

We had four projects being undertaken by expedition members including reconstructing past temperatures, diatom ecology, and pollution. Our results were looking at changes ranging from the present to 12,000 years ago and therefore varying factors are at play over this timescale. The temperature reconstructions found a long-term link between changes in the North Atlantic and Sayan Mountains’ temperature, whilst the diatom ecology study found that a significant regime shift in diatom community composition had occurred around 3,500 years ago. The pollution study also established the presence of anthropogenic pollution at the study site, though at relatively low levels.

Cleaning of Kascadnoe-1 core at the Institute of Geochemistry labs, Irkutsk.Â

Did everything go as you expected?

We knew that organising an expedition would certainly be a significant and challenging undertaking, but that if we were able to pull it off it would also be an unforgettable experience. Whilst the pre-expedition work was certainly hard at times, the reward of being able to conduct fieldwork of our choosing in a remote location such as Siberia was really the culmination of everything we wanted our geography degrees to be – even if it did rain a lot!

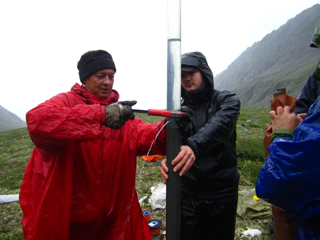

Draining water from Kascadnoe-1 core

Do you have a highlight from your fieldwork?

A standout moment was when we first rowed our inflatable boat to the centre of our study lake to collect data for our fieldwork. From the lake centre we felt an amazing feeling of awe as we absorbed a view seen by so few before us, of towering mountains, volcanoes and pristine water. Upon successful collection of the sediment cores from the lake our rowing trip was perfectly concluded by the offer a cup of ‘che’ (tea in Russian) after arriving back at the lake shore!

What will you take away from your fieldwork? What’s next?

We have gained a greater understanding of how to tackle organising the logistics of a project of this scale and duration, including applying for funding, organising accommodation and travel with Russian colleagues, and planning a methodology to collect data when in the field. Skills such as these are invaluable for us going forward, as several of us are undertaking various Masters' programmes to move into the environment sector, and Meg is going on to teacher training.

The team with collaborators from the Vinogradov Institute of Geochemistry and Institute of the Earth’s Crust (Alexandr, Meg Picken, James English, David Warnes, Dr Ivan Filinov, Dr Alexandr Shchetnikov, Harry Williams). Image: Harry Williams

Geographical Fieldwork Grant

This project was supported in part by an 91ÇÑ×Ó Geographical Fieldwork Grant, Neil Thomas Proto Award and the Edinburgh Trust, and the Gilchrist Educational Trust.